In 2012, Venkatesh Rao wrote a 3-part series of articles entitled "Entrepreneurs Are The New Labour", published in Forbes, in which he made some observations about current-day entrepreneurship. [0]

In this article, I'll preserve my own copy of this series.

Entrepreneurs Are The New Labor: Part I

For the last few months, I've been cautiously testing a radical-sounding hypothesis on smart people: entrepreneurs are the new labor. Or to put it in a more useful way, the balance of power between investors and entrepreneurs that marks the early, frontier days of a major technology wave (Moore's Law and the Internet in this case) has fallen apart. Investors have won, and their dealings with the entrepreneur class now look far more like the dealings between management and labor (with overtones of parent/child and teacher/student). Those who are attracted to true entrepreneurship are figuring out new ways to work around the traditional investor class. The investor class in turn is struggling to deal with the unpleasant consequences of an outright victory.

In the small and incestuous technology world, where I make my living shouting advice from the peanut gallery, standing behind politically charged statements like this can do a good deal of damage, so I've been wary about sharing my views more publicly.

To my surprise though, I found a lot of people agreeing with me. In fact, many confided that they'd been thinking the same thing themselves, and even offered more radical formulations than my own. By contrast, I found very few people seriously arguing for the obvious antithesis (a sort of gung-ho "everybody can be a genuine entrepreneur" sentiment, which I find to be a vacuous rationalization of grim economic realities.)

The implications of this new state of play are extremely important, and extend far beyond the startup world to the economy at large. This is not just another quickie X-is-the-new-Y meme. Which is why it is going to take me some time to develop the arguments carefully. In this first of a three-part series, I will cover the history of this particular entrepreneurs-turning-into-labor pattern, which dates to the 19th century. In Part II, I will apply the pattern to our times, mutatis mutandis. In Part III, I will try to look ahead at how the landscape might evolve.

The Politics of the Shift

I should note that none of this is news to anybody even marginally involved in technology entrepreneurship. This entire three-part series is merely my attempt to assemble arguments made piecemeal by many others, into a coherent whole. But I suspect people far from the entrepreneurial world have no idea that all this is going on.

"Entrepreneurs as the new labor" is not necessarily a bad thing, unless you are among those who are attracted to the "masters of the universe" cachet rather than the substance of the "entrepreneur" label. There is dignity to labor just as there is romance to entrepreneurship.

There are many good things about the shift to a de facto management-labor game. Such a game is sorely needed as industrial models collapse and the work of defining an Internet-era corporate landscape, with new institutions capable of organizing work for a much larger population, begins.

There are still enlightened investors who use their new unchecked power wisely, and there are still entrepreneurs who are wily enough to stay inside the system and play the game on their own terms.

But for the most part, the collapse of the balance of power is not a good thing. Nor is a significant disconnect between nominal and actual narratives defining the lives of a significant and important population.

The good news is: this has happened before (in the late 19th century), and the last time around the system naturally self-corrected and defined a new labor class on its own terms, with the "entrepreneur" label being reclaimed by those it actually described. In the process, a new middle class was born. This was an external side-effect as far as entrepreneurs were concerned, but the main outcome of interest to everybody else. That's the big hope on the horizon here: that the current travails of the entrepreneur class might eventually end with the formation of a new middle class to replace the one that is currently being gutted.

The transition was not without considerable pain, so we can and should learn from the previous episode and speed up the correction, this time around, hopefully with less pain and overcompensation. For those of you tempted to read this series as a blanket tarring-and-feathering of the investor class, keep in mind that they play an essential role, and that things aren't particularly pretty when entrepreneurs are dominating investors either.

Real entrepreneurship can return, and those playing the new management-and-labor game can learn to understand themselves more clearly, with a new management-labor narrative, instead of an overloaded investor-entrepreneur narrative.

But however you read what is going on, such a shift is politically charged. I like to kid myself that I am a political neutral on these matters, so I'll restrict myself to sketching out the contours of the new landscape, and leave you to form political opinions about it.

The Entrepreneur Class Today

Before I proceed, I should offer a very important qualification. By entrepreneurs I mean specifically the narrow class the term has come to define in the last decade: specifically technology entrepreneurs who start companies to build products or services with some sort of technological innovation at its core, with the Internet playing an important role in the venture.

This might seem to be a very narrow definition, but due to the dramatic ongoing impact of the Internet in every sector ("software eating everything"), and the collapse of traditional employment paths, this restricted class of entrepreneurs is quite significant in terms of both numbers and economic impact, and is growing rapidly.

My thesis specifically does not apply to other sorts of entrepreneur: the kind who start risky but non-innovative businesses of the coffee-shop variety, or the kind who steer a staid old family business onto an aggressive growth path. In recent years, the term entrepreneur has been glamorized, valorized and mapped to the technology-startup type entrepreneur, so I am using the unqualified term for simplicity.

And within this class I am specifically refering to the sub-category known as hustlers today. Technology startups typically have a hacker-and-hustler founding pair. Though the hustler can often do some hacking as well, the term has come to mean the person leading marketing, product management and fund-raising activities in the early stages.

So a more careful statement of my thesis would be: non-technical hustler founders of technology startups are the new labor.

What about the technical co-founders? Because of their very different risk exposures, compared to hustlers, they end up on a different path that effectively makes them mercenaries rather than entrepreneurs, a path that generally promises smaller jackpots, but better expected outcomes and survivability.

In brief, whereas hustlers have gradually been losing their information advantage with respect to investors (resulting in the balance of power collapsing), hackers have generally been gaining information advantage with respect to both, as Internet-era technology has gotten more complex and specialized. But their advantage does not lend itself well to being directly wielded. So the power of the technical community is organizing itself in other ways, which I covered in my earlier post on the rise of developeronomics. [1]

Before we dive in, here are two versions of the argument that make my views seem almost moderate by comparison. I want to call these out so you can calibrate various positions in these debates (all the way from "everybody is an entrepreneur" cheer-leading to "evil VCs pwn innocent founders" despair).

- A friend who works at a hedge fund and is starting to dabble in startups on the side wanted a quick primer from me on the popular Lean Startup model. After outlining the basic idea, I added some of my own cautious critical commentary. My friend immediately leaped to the conclusion that I'd been unconsciously resisting: "So you're basically saying that lean startups are great for investors, and not so great for entrepreneurs." (He also said "bwaahaahaa!".)

- Another friend, a battle-scarred tech veteran, reacted to my views with a metaphor that made even me cringe: "So incubators like Y-Combinator are basically a cloud resource for investors, from which to source interchangeable hustlers, who are prized primarily for their youthful energy rather than any deep market knowledge". So much for the vaguely romantic notion of startup-founding as being somehow qualitatively different from interchangeable drones in a cubicle farm. Different farm, same metaphor.

I think these versions of the argument overstate the case, but viewed as rhetorical exaggeration, they do make valuable points. Lean startup models, applied with wisdom, can work for entrepreneurs. Applied naively, they become back-seat driving mechanisms with which investors can micromanage startups, to the detriment of both. But the model, being a product of our peculiar times, has the asymmetric balance of power between investors and entrepreneurs wired into its very DNA.

Startup incubators and angel investors can sometimes seem more like outsourced job-training for big companies, or even a substitute for college and graduate school respectively (in fact, many commentators proudly advertise that idea, and the "batch" and "graduating" language is a dead giveaway), but there are people graduating with genuine entrepreneurial skills.

So let's take a look at the entrepreneurs-are-labor model. It is useful to start with the nineteenth century steel industry where a similar emergence of a labor class from an entrepreneurial class happened, with different outcomes for the hustlers and hackers.

The Nineteenth Century Steel Game

In attempting to make sense of today's startup scene it is very useful to reflect on the evolution of the global steel industry in the nineteenth century, as it moved from its startup phase in England to its scaling and growth phase in America and Germany (similar things happened in mining, oil, railroads, telegraph and agriculture and machinery).

In the process, a two-tier reorganization occurred, reflecting the diverging paths of the hackers and hustlers of industrialization.

In the first tier, the artisan class of steelmakers (the hackers of their age), that had organized itself in intricate guild-like structures, gave way to two sub-classes: a mercenary-minded scientifically trained engineer class that organized itself into professional associations, and a manual labor class that organized itself into the modern labor movement.

The finest example of the former was probably Alexander Holley, a sort of polymath-engineer Elon Musk of his time, but with more of a pure engineering mind. He was the greatest steel-plant designer of his time; the uber-10x-hacker of steel-making. When Andrew Carnegie turned his attention to steel, and raised $700,000 to build the pioneering Edgar Thompson plant, Holley stepped up immediately to handle the technical end. Charles Morris describes the event in The Tycoons:

Holley was engaged almost immediately; he had made the first contact himself as soon as he heard of the new plant. His offer -- $5000 for the drawings and $2500 a year for construction supervision -- was one that could not be refused.

It is critical to note two things about Holley's role. First, he negotiated a significant (for the time) but low-risk remuneration package (amounting to about 1% of the capital raised, but as cash rather than equity). Second, he made sure he wasn't tied to Carnegie via risk-capital, and offered his services as a highly paid mercenary, within a time-bound model. He was what we would call a rent-a-CTO today.

It is critical to note what he was up to on another front: he was a major figure in the founding of the ASME (the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and the model for later engineering associations in newer disciplines) in the 1880s. He had consciously decided to forgo the entrepreneurial path, and thrown his lot in with the emerging mercenary technologist class.

Holley's model came to define the engineering profession as it evolved: a community that organized itself along the lines of the scientific societies of the day, and arrogated to itself the authority to define, evolve and steward specialized knowledge of technology. Perhaps most importantly, engineers after Holley allied themselves with the owners of capital but maintained a suspicious arm's length relationship with them, using the instrument of professional associations, which cut across corporate boundaries and serve to liaise with academia. By organizing themselves in this manner, technologists took themselves out of the entrepreneurial equation for the most part, but retained an autonomous voice and a capacity to constrain the game through mechanisms like standardization and stewardship of commons knowledge.

Early engineers like Holley were mercenaries with no fixed loyalties to employers, businesses or markets, but a strong loyalty to a technical discipline and scientific methods of engineering. It wasn't until a few decades later that they turned into standing armies, as universities began churning out engineering graduates in larger numbers.

Their cousins on the shop floor suffered a different, less happy fate.

From Bankrupt Artisans to Modern Labor

The world of artisans was fundamentally at odds with the world of the large corporations. Artisans preferred to arrange their internal technical and economic affairs via what we would call internal markets today. This made each senior artisan something like a small business owner or tenured professor, managing a certain amount of risk, negotiating pay dynamically with bigger capitalists and the government, and contracting out work to other artisans. But these seasoned artisans had limited ambitions, they were not really entrepreneurial enough to want to scale to large operations.

Artisans were entrepreneurs within ecosystems around relatively small corporatized cores. Theirs was an intricate world of dozens of narrowly defined crafts, arranged in a production network. In the early years, larger business owners had no choice but to work within this model. It was a complex but relatively stable world defined by a network economy that was extremely rigid in some ways, and fluid in other ways.

But once science entered the picture, and engineers effectively took control of deep knowledge and forked off a community largely allied with owners of capital, the days of the residual artisan class were numbered. They had been intellectually bankrupted.

As Morris recounts the story, through the eyes of a British team surveying the American steel industry in the 1880s:

The skills required in the modern factory were invented and controlled by the employer, and didn't take years of apprenticeship to acquire. The [British] visitors were struck by the short training periods required for raw hands in American mills; one Carnegie executive claimed he could make a farmboy into a melter, previously one of the more skilled positions, in just six to eight weeks. Integrated operations also eliminated the last vestiges of internal contracting.

I don't want to get ahead of myself, but in case you can't see where this is going, the analogy is to modern incubators promising to turn anybody into an entrepreneur in a weekend, week, or summer. More on that in a bit.

But the result of the new scientific models of manufacturing was modern labor. The residual artisan class could no longer rely on privileged access to an illegible knowledge base and opaque organizational order to protect itself. That weapon had been taken over by the new class of engineers. They did the only thing they could: come together in solidarity in larger numbers to monopolize access to labor supply. If the engineers withdrew from the poker game of business, the remaining artisans no longer had enough stakes to stay in the game as individuals.

They had been commoditized. The result was modern labor unions. Muscle farms. Or muscle clouds. The phrase collective bargaining emerged to describe their new role in the game. For the most part, they had been reduced to interchangeable parts. Autonomous control over supply, via aggregation in unions, became their only source of power.

What about the hustlers? Ironically, bankers managed to do them what they had done to the artisan class: split them into new mercenary and labor subclasses. This is the story of the second tier.

Hustlers versus Bankers

In the second tier, the hustler class of new-money industrialists produced a first generation of Robber Barons, and then an asymmetric balance of power between bankers and second-generation hustlers who aspired to Robber Baron level fortunes (egged on by Horatio Alger narratives), but ended up as the tame new middle class. How did this happen?

Carnegie was an old-school, large-scale hustler, like his contemporaries, Rockefeller, Jay Gould and Vanderbilt. Like them, he had some technical knowledge, but delegated most of the technological work to the new engineering class. Where he excelled was in his understanding of the murky emerging market structure and state of play. Like his contemporaries in the hustling game, he made something of a specialty of maneuvering around bankers in the world of finance, and found a certain vicious joy in doing it well (frontier hustlers swindling East Coast bankers before the rise of the telegraph was a common occurrence).

For approximately three decades following the Civil War, a tenuous balance of power situation prevailed, with canny real entrepreneurs like Vanderbilt, Rockefeller and Carnegie facing off against bankers like J. P. Morgan who were trying to do to the new mega-corporations what the Rothschilds had done to nation-states a century before: control them with money. Transitional figures like Jay Gould were starting to turn into hybrid financial operators and business managers: adept at both railroad Go-playing and stock-market manipulation.

But by around 1910, the balance of power had collapsed (as had the political balance of power in Europe, a not-unrelated development). The Robber Barons slowly withdrew from the scene to enjoy their great fortunes and redeem their tarnished images with good works.

In 1901, in an event charged with symbolism, J. P. Morgan managed to buy Carnegie out of the steel industry, to create US Steel. It was a feat Morgan and his crew would repeat across the industrial landscape, arranging new equilibrium conditions and regulatory mechanisms in one sector after the other, filling in for a non-existent central banking function (the Federal Reserve was created in 1913, marking the start of a whole new story).

How did the bankers win? In large part it was because in the balance of power, hustlers lost their main weapon: specialized and indispensable knowledge of murky emerging markets. On the other side, the bankers gained control of the new infrastructure, which were primarily financial beasts in their mature form. Since the newer hustlers needed the infrastructure (for example, hustlers taking advantage of oil, railroads, telegraph and electricity to build businesses in the new booming urban centers), they were at the mercy of the bankers.

The old-school hustlers were left with no leverage at the negotiating table with the owners of capital, while at the same time being at their mercy, instead of at the mercy of Wild West nature. In terms preferred by economists, a situation defined by a principal-agent problem (such as you hiring a doctor or car mechanic who gets to both define your problem and figure out what to charge you for fixing it) was replaced by a much simpler employment relationship: would-be hustlers found themselves being turned into professional, generalist managers.

Whereas in the 1870s, East Coast and European bankers had no option but to trust deeply knowledgeable experts on specific illegible emerging markets such as oil and steel, by the 1900s, bankers could do to wannabe-Carnegies what people like Carnegie themselves had done to the artisan class: extract the knowledge they brought to the party and neutralize its use at the negotiating table. The knowledge itself was turned over to the stewardship of yet another new mercenary class: marketers. Marketers were skilled at using the new emerging media (the mass-market newspapers that had been enabled by the development of cheap printing technologies in the 1890s) to sell, but not particularly interested in the full-spectrum risk-taking required of true entrepreneurs. The story of this mercenary class, which created the modern consumer economy on the foundations of 19th century technology infrastructure, is fascinating, but we won't get into it (the excellent 4-hour documentary mini-series, The Century of Self, does a great job of telling that story). Again, to peek ahead, we've seen a similar rise in new media models.

Instead of hustlers telling credulous investors what returns they could expect, investors told hustlers what returns they had to deliver, based on their own analysis of information made freely available by new media outlets working off the power of the telegraph. They knew enough to understand how hard they could push without breaking things (the rate of return they demanded would soon ossify into a ritualized expectation of stable growth rates, a big enabler of the rise of a middle class that could basically withdraw from the risk frontier).

The Gilded Age End Game

The game was over. Artisan hackers and old-school hustlers had been knocked out of the game, and transformed into engineers, laborers, marketers and professional managers in the process. The bankers had won (historically, this has always been the case; the only force capable of beating bankers in a technology-wave end-game is politics, backed by physical military force, a scenario that played out in Germany and Japan).

In information-theoretic terms, what happened was simple. Before, there was a chaotic and illegible new world of market and technical knowledge, owned by hustler and artisan (hacker) classes respectively. Each of those classes was able to use the illegibility of its domain to outsiders to create principal-agent situations to negotiate with investors on advantageous terms.

After, this knowledge became codified and institutionalized into a two level hierarchy, each with a specialist and generalist component. Artisans turned into laborers (generalists) and engineers (specialists). Hustlers turned into marketers (specialists) and professional managers (generalists).

The defeated players who retained some individual leverage turned into the new professionalized and mobile middle class. Those who didn't, turned into either blue-collar or white-collar generalist labor. The general principle was simply that money tamed silos of information in most-legible-first order so that it was no longer in play at the negotiating table. Once all information had been neutered via equilibrium arrangements, finance became, once more, the game of zero-information-advantage gambling it always wants to be.

The 1870s - 1930 story should sound very familiar to anyone over thirty. We've basically lived through a compressed and highly accelerated (by a factor of 2x to 3x) version of the same cyclic pattern, starting around 1979.

We will explore this story, which is now entering its end-game phase, in Part II.

Entrepreneurs are the New Labor: Part II

When you examine the 19th century pattern of transformation of an entrepreneurial class into a labor class, which we covered in Part I, the conclusion is obvious: a labor class emerges when privileged knowledge is commoditized and institutionalized in ways that make it basically useless as negotiation leverage with the investor class, leaving supply aggregation as the only path left for the extracted and intellectually bankrupted class.

The extracted knowledge is placed under the stewardship of a new mercenary class that eventually turns into a domesticated new middle class (this pattern is not just restricted to the 19th century; variants have played out at least a few times before in world history).

This is an intrinsic definition of labor rather than an extrinsic one based on historical specifics. What are the classic symptoms that such a transition is happening?

- The emergence of a new, specialized knowledge worker class with mercenary tendencies, from an older class. This eventually becomes the new professional class.

- Increasing solidarity in the residual generalist class in its relationships with the financial class. This eventually becomes the new organized labor class.

Both developments have occurred in the current technology startup environments, and the differing fates of hackers and hustlers are illuminating here: hackers are turning mercenary, hustlers are turning into the new labor. Let's see how.

The New Engineers

Hackers are doing to traditional engineering what engineers themselves did to the artisan class a century ago. Except this time around, the residual labor class they leave behind is not people, but computers that replace traditional engineers.

Where engineering in the 1880s organized itself around lines suggested by the physical sciences, the new technologists are organizing in new ways, along lines suggested by the cognitive, aesthetic and social sciences and arts: computer science, psychology, social psychology, user-experience and design. We won't get into these new organizational models, other than to remark that they are going to look superficially similar to the ASME or IEEE, but will be drastically different internally. That is a subject for another day.

As software eats the world, every sort of engineering (and indeed, every sort of profession organized along lines suggested by the physical sciences, including fields like medicine) is becoming effectively a branch of computer science. To take my nominal, mostly abandoned profession of mechanical engineering, much of the intelligence is now in CAD tools. Mechanical engineering is no longer about mechanical engineering knowledge per se, but about capturing a century of codified knowledge in software systems (to my fellow mechanical engineers who still practice: when was the last time you computed equations of motions by hand?).

If you are in a traditional engineering discipline and are not programming computers to do what you were taught to do, your days are numbered. I recall my computer science peers from college creating a t-shirt for themselves with the slogan, "I'd rather write programs to write programs than write programs". That ethos of going meta now affects every technical discipline. It now makes more sense for the mechanically talented to write programs to do mechanical engineering than do mechanical engineering.

The residual traditional engineering types who eschew computers will increasingly find themselves in the position of 19th century artisans who failed to reinvent themselves as engineers: the knowledge they need will move into the new tools, and they will become the new blue collar class. Actually, it is going to get worse. They may not be needed at all. At that level, computers are the new labor.

Both designers and hackers are far more likely and able to hedge their options and cultivate horizontal relationships with others who can help them develop and preserve their skills within emerging professional organizations, rather than vertical skills in the market that can help them contribute to the success of a single enterprise. The very best gravitate to tool-making, open-source projects and other positions of horizontal influence.

When startups are founded by strongly technical types, they are often explicitly designed as vehicles for acqui-hiring: startups that consciously develop products and services that make for exceptional acquisition properties for larger companies. Such companies are often accused of building features rather than products, but that is the whole point. The founders are looking for fast-track short-cuts to good jobs, and some mercenary freedoms, not a life of adventure.

Incidentally, there is no more contentious topic in the startup world today than acqui-hiring, and much of the noise is caused by semantic confusion. If you are attached to the label "entrepreneur" and the increasingly inappropriate archetypes associated with it, you will hate the idea of acqui-hiring. If you see it as a reasonable emerging model of hiring replacing a broken one, you will like it. Acqui-hiring is only a problem if you are attached to specific labels.

For this pattern to emerge, the Robber Baron era of our current technology cycle has to have matured and plateaued, and big companies must be in the market for incremental innovations that enhance their main offerings. If you were surprised by the $1 billion Instagram acquisition under conditions that appear close to market blackmail, you shouldn't be; Rockefeller made many such overpriced acquisitions on his way to world dominance in oil, and a veritable cottage industry emerged to take advantage of his world-conquering impatience: people would set up obviously worthless refineries just to get bought up by Rockefeller. And he would make many of them managers. Acqui-hiring is not a new phenomenon.

If anything, Zuckerberg is to be commended for thinking at Rockefeller levels -- not getting sucked into minor battles in small skirmishes along the way to much bigger things. He is thinking about the game at the right level. It was probably worth $1 billion to avoid a potentially costly and distracting marketplace battle over a key future battleground (control over the smartphone camera, the first sensor in the emerging Internet of Things). When you are Facebook, trying to convince the world that you are the gateway to a $100B market (not very well at the moment) you have to pick your battles.

In this environment, a world apart from the early frontier days of the Internet, hackers today universally exhibit a certain mercenary sensibility, cannily juggling multiple offers, playing judge in hustler beauty contests at hackathons, planning acqui-hire trajectories, and in general maximizing their value as the stewards of the new body of technical knowledge. And often hanging their hustler buddies out to dry.

The Fall of the Hustler

Hustlers on the other hand, increasingly behave like a new labor class. In fact, my first suspicions that this transformation was underway were sparked by a sudden shift in perception of hustlers.

Not to put too fine a point on it, true hustlers are generally despised by those who work closely with them.

In our time, overnight, they turned into media darlings. They began to be lauded as heroes, saviors of the economy, creative geniuses, even models of patriotic virtue. Even Obama and Romney agree that Entrepreneurs Are Great. That sort of valorization is characteristic of labor movement rhetoric.

True hustlers, as they steamroller over markets, rapidly acquire reputations of being arrogant, autocratic, sociopathic and generally lacking in the kindness department.

People work with hustlers because they are forced to, with or without being consciously aware of it (hence the "hustle" in hustler) not because they want to. Our age has been no exception. Bezos, Gates and the late Jobs have generally been viewed much like Rockefeller, Carnegie and Vanderbilt were a century before them. The mellowing of their images in later years is generally due to careful PR and charitable works (or in the case of Jobs, a certain romanticization due to untimely death).

Nobody praises true hustlers as heroes or talks about them as a large, massed class of interchangeble Jolly Good Fellows. Or puts them up on a pedestal comparable to that reserved for soldiers. Rather, they are regarded as rapacious predators. Even by bankers. They represent extreme self-interest, so if the fact that they currently share a pedestal with soldiers, who represent extreme self-sacrifice, doesn't strike you as unusual, you aren't reading the situation closely enough.

Yet, that is exactly what has been happening to hustlers in the last decade. You have to choose between two readings of the sudden shift: either entrepreneurs have been such praiseworthy souls all along, and we've only just recognized their value, or the new entrepreneurs aren't entrepreneurs at all, but wantapreneur-laborers being humored by a victorious investor class.

Again, this is not new; post-Robber Baron era young people were fed similar self-perceptions via the Horatio Alger stories; it is notable that Alger had his breakthrough hit in 1868, by which time the major Robber Barons were already well into their later careers. Rather than create more entrepreneurs, the Horatio Alger stories mostly helped fuel the emergence of new labor and middle classes.

The saccharine rhetoric around entrepreneurship today hides an extraordinarily rapid behind-the-scenes actual devaluation of the hustler class in real terms. As the cost of starting new startups has crashed, so has the cost of hiring "CEOs" to run them. Silicon Valley even has cartoons doing the rounds, of homeless CEOs holding up signs begging for CTOs to join them.

In fact, the standard now is a sort of ennobling poverty marked by the rent-and-ramen formula that members of the class typically accept as a sort of badge of honor (if you took everybody with the CEO title at face value, trust me, you'd feel so sorry for the median homeless CEO that you'd argue for higher wages).

About the only thing distinguishing them from waiters in Hollywood is the stock they own, which have approximately the same chance of being worth anything as a Hollywood waiter has of landing a breakthrough role in an audition.

Let me hasten to add that this situation is a perfectly natural one. The hustlers of today really don't deserve the outsize compensation packages of hustlers from 10 years ago, because they typically bring no unique and indispensable knowledge of murky markets or technologies with them. They just bring resourcefulness, youthful passion and energy.

Some of the signs are well known and widely acknowledged (I've never had anyone seriously object to these points).

- The resemblance between the idea of "standardized term sheets" for early stage venture investments, which emerged a few years ago, and labor union contracts, is unmistakable.

- There are striking similarities between organizations like Adeo Rossi's TheFunded, and early labor unions at the turn of the last century.

- The transformation of fund-raising activities from genuine negotiations between evenly matched parties to "pitch cultures" that hew to ritual "know your place" expectations on the part of investors (one can hardly imagine a Carnegie or Rockefeller anxiously fretting over what bankers might want to hear at a pitch meeting or anxiously studying how-to books on pitching and business plans; they'd have just walked into the room, hours late, with blackmailer swagger).

The change in perception of the investor class from a peer-adversary class to a Dark Side or Godfather class.

- The sharply declining age of wannabe entrepreneurs. Instead of putting in a decade or more to learn a market, accumulate a significant bootstrapping warchest and a good hand of unfair advantages to play with, we now find fresh college graduates jumping straight into the entrepreneurship path.

These overt, punch-in-the-face signs of the ongoing transformation are not surprising to anyone even remotely involved in technology.

Let us explore some key elements of the emerging new state of play that are perhaps not obvious to the mainstream world.

From Tacit Hustler Knowledge to Student Labor Education

If Carnegie's executive boasted that he could turn a farm-hand into a melter in just six to eight weeks, today's hustler-educators sometimes claim to achieve a similar transformation in a weekend. There are a range of offerings from "startup weekends", to week-long courses, to the prototypical Y-combinator style summer program to "entrepreneur MBA" offerings.

The fascinating thing is that these boasts are not idle. These programs are generally not vending snake oil. The knowledge on sale is mostly the real deal. The Truth. So why is there a problem? It's just not The Whole Truth.

Entrepreneurship is three things: a set of business skills, a set of political skills, and a stash of hoarded unfair advantages, held in reserve for the right opportunity. When the latter two vanish, it becomes merely a teachable generalist skill, rather than a cultivated talent for successful risk-taking.

You can codify the first, but only time and experience allow you to develop the other two elements. Almost by definition, you cannot codify political skills (politics is the art of hacking the codified), and unfair advantages obviously cannot be codified, merely hoarded.

The first (and least important) element, entrepreneurial business skill, has been codified, and is being sold as the whole package. This phase of unionization is much like the rise of universities and student unions after the maturation of labor unions (it is significant that many of the major Robber Barons -- Vanderbilt, Carnegie and Rockefeller among them -- established major universities. The Morrill Land Grants simultaneously created the Public University system, and universal high school education was in place by around 1910).

An element of the accelerated technological cycle this time around is how quickly the connection to education has appeared. The last time around, it took something like 30 years. This time it has taken less than 10.

Organizations like Y-Combinator look less and less like startup incubators and more and more like novel alternative universities, offering the hustler class a sort of professional hustler training similar to marketing or sales training in companies like Vicks in the 1920s and 1930s (beautifully chronicled by William Whyte in The Organization Man).

The Politics of Codification

Codification of tacit knowledge does not codify political skill, but is never an apolitical act.

All codification is political. Knowledge is captured and codified in ways that benefit a specific class. In the case of previously tacit entrepreneurial knowledge, the codification has been carried out to benefit investors. The biggest piece of such codified knowledge is the well-known Lean Startup model. While it functions roughly as advertised in a narrow sense, its real political significance is in the control structure it subtly encourages, which increases transparency to investors (and sundry outsiders).

For example, by encouraging explicit, written market hypotheses and undisguised (and sometimes even publicly articulated and defended) business model shifts known as "pivots", it allows investors far greater visibility into operational realities, and therefore, better back-seat steering control via board seats. It takes a sophisticated entrepreneur to use the model for its strengths, and still create a realistic balance of power with investors.

Natural true-entrepreneur instincts towards guile and marketplace deception to outmaneuver the competition, and guarded relationships with investors, are suppressed in favor of allowing investors to easily scale their control authority across many cheap startups.

Again, this is neither good nor bad. It is merely reflective of the new distribution of privileged information. With the rise of a vibrant new technology blogosphere, paralleling the rise of the newspapers in 1900-1910, it is far harder for hustlers to hide unfair advantages against prying investor eyes.

When Y-Combinator recently announced that it would accept applications without ideas, the evolution hit its natural plateau. To anyone operating by the education analogy, the move made complete sense: it was a "you don't have to declare a major immediately" moment in institutional evolution.

So nobody was particularly shocked when, immediately following the announcement, it became clear that MBA types were starting to eye Y-Combinator as a credentialing organization, to augment the fading luster of MBA degrees (in resume-speak, entrepreneurial is the new strategic).

Some entrepreneurship watchers feigned shock and distress, but for the most part the development was not unexpected. It wasn't that MBA programs were inching closer to startup turf. It was the other around.

Decline in Investor-Entrepreneur Conflict

A second key element in the evolving landscape is the sharp decline in conflict between the investor class and the entrepreneur class. Earlier in a large-scale entrepreneurial cycle, the debate between bootstrapping models and investor-funded models tends to be fierce and real.

Rockefeller, for instance, never trusted Wall Street money and mostly used internal and debt financing to grow Standard Oil, until he became powerful enough to exercise his own control over Wall Street. Vanderbilt was similar.

Even a few years ago, you could find people espousing fierce sentiments and deep reservations about OPM (other people's money). Much of that depth of sentiment appears to have vanished.

Today, bootstrapping vs. venture-funding has been subtly reframed as a lifestyle-business vs. growth-business debate. For those new to the subtleties of these debates, growth is an independent axis. Bootstrapping can create large businesses, and with the right kind of investor expectations (read: deliberately decoupled from Wall Street and its Wild West outposts), investor-funded businesses can remain small and lifestyle-sized too.

In accepting venture funding as the de facto model for growth and scaling, entrepreneurs as a class have mostly handed control over how to create and manage growth to investors, much as most sectors gave in to J. P. Morgan's crew a century ago.

There are fewer and fewer figures like the Sean-Parker-coached Zuckerberg, who turn the entrepreneur-investor game into a real contest. At least in the early stages, investors entirely run the game. Hustles like the recent Color.com debacle, where entrepreneurs (seemingly) manage to pull a fast one on investors, become increasingly rare. Today, Color.com type stories are the exception. Ten years ago, they were the rule.

The Curious Fate of Serial Entrepreneurs

The third key element is perhaps the most curious. This is the fall of serial entrepreneurs, which most people see as the rise of the angel investors. But the fall aspect is actually more interesting (I am tempted to make a "fallen angel" joke here, but can't think of one).

Until a few years ago, whether you succeeded or failed, serial entrepreneurship was the main pattern (the other one being the founder-to-VC Dark Side switcheroo). It made perfect sense for restless and exploratory true entrepreneurs craving excitement rather than returns, and also made sense because all the education required was acquired through apprenticeship rather than codified models. You needed multiple experiences before you could learn the business and political skills and accumulate enough of an unfair advantage.

The third key element is perhaps the most curious. This is the fall of serial entrepreneurs, which most people see as the rise of the angel investors. But the fall aspect is actually more interesting (I am tempted to make a "fallen angel" joke here, but can't think of one).

Until a few years ago, whether you succeeded or failed, serial entrepreneurship was the main pattern (the other one being the founder-to-VC Dark Side switcheroo). It made perfect sense for restless and exploratory true entrepreneurs craving excitement rather than returns, and also made sense because all the education required was acquired through apprenticeship rather than codified models. You needed multiple experiences before you could learn the business and political skills and accumulate enough of an unfair advantage.

Startup veterans, for the most part, move on to second careers as angel investors, from which new position they now compete with venture capitalists, often trying to engineer early-exit scenarios at lower multiples, and effectively allying themselves with the big acqui-hiring companies against the traditional VC class. You could say the smaller angel investors in particular, are effectively the new outsourced middle managers for big companies in the acqui-hiring market. In a curious parallel development, effective middle managers within large corporations increasingly act like angel investors internally.

This is a major new pattern, and has been much talked-about, but what is not talked about is the pattern being replaced. Every new angel investor gained is one pure serial entrepreneur lost. People who stay purely on the other side of the table from the money side over multiple projects are becoming rare. These means there are fewer pure entrepreneurs around with experience.

It is difficult to find an analogy for this development in the 1910s, since that era was marked by high-capital-needs opportunities (which were still, however, much lower than the capital needed for businesses like steel or railroards). History repeats itself, but never quite exactly.

Once they've broken out of the entry level of the game, where they are part of the student-labor hustler class, true hustlers who find themselves locked out of bigger hustling opportunities, increasingly tend towards mercenary hedging like their hacker cousins, via multiple small, low-stakes "studio" projects, while they wait for the next opportunity to engineer a bigger move.

The interesting game has now shifted one level up, to the relationship between VC firms and their Limited Partners. This is similar to the J. P. Morgan endgame of the last entrepreneurial era. The difference is that there was no formal VC class back then: merely investment-minded second-tier deal-makers who did their wheeling and dealing in the interstices of the stock market, Robber Baron and small-entrepreneur worlds. And of course, there is nobody with J. P. Morgan level clout and stature today; the economy has grown too big and complex for one individual to conduct the orchestra.

But those minor differences aside, it is substantially the same endgame.

And as in that case, there are clear signs that the Big Brothers might win out and arrange some sort of wide-ranging regulated equilibrium with the aid of the government.

In this case, the Big Brothers are the Limited Partners, whose new strategic position (which has been evolving for some time) has now been openly declared in the recent, and much discussed, Kauffman Foundation report indicting the VC industry for poor returns over the last decade, and suggesting reform on the LP side of the fence to counteract it.

Suffice it to say that the big guns are about to do to VCs what VCs have done to entrepreneurs. I suspect it might involve an alliance between big Internet-era companies like Google and Facebook, and the Limited Partner world, designed to rationalize and institutionalize a de facto world of acqui-hiring-on-top.

Other Signs

I don't have time to go into other signs that clearly fit into the "entrepreneurs are the new labor" model. But they include:

1. The strange rise of "social" (as in do-gooder social-mission, not social media) startups and the demonization of the far more natural wealth-now-philanthropy-later model practiced by the Robber Barons and, more recently, Bill Gates. This closely parallels the rise of what William Whyte called the "social ethic" in the new Organization Man world that emerged after World War II, where a script based on communitarian ideals of "belongingness" and rejection of no-holds-barred wealth-seeking marked the maturation of the middle class.

2. The extremely clever redefinition of the word "passion" to mean a sort of uncritical, unreflective, high-energy drive focused on a creative rather than canny self-image. The result is a sort of go-all-in/go-all-out expending of all resources and advantages in a single opportunity, within which debate and dissent are easily labeled second-guessing and lack of drive. This sort of unhedged and single-minded devotion serves investors rather better than it does entrepreneurs.

3. The replacement of a lifelong narrative with an episodic startup-to-exit narrative that encourages entrepreneurs to not develop and cultivate assets that might have different kinds of value in future.

4. The slow shift towards entrepreneurship directed at "first world problems" and a new "experience consumerism" and slackening of interest in harder infrastructure innovation. This is similar to the huge boom in "product consumerism" that started around 1890 and lasted through the 1970s. There is much hand-wringing about entrepreneurs not solving "real" problems that suddenly seems besides the point if you view what they are doing as serving an emerging post-(product) consumer middle class devoted to experience-consumption. That this class is currently fairly small and economically insecure relative to the vanishing old middle class does not mean that is non-existent. Instagramming, food-truck finding and location-aware dating are the photography (Kodak: 1889), washing machines (1930s) and toasters (1920s) of our age: building blocks of a new normal for a self-absorbed new middle class.

5. The rapid rise of "lifstyle design" as a quasi-entrepreneurial pattern of behavior on the part of those with modest ambitions (achieved via either bootstrapping or kickstarter-scale investments). This is best understood as a reaction by those who are inhabiting temporary mercenary roles in the economy, while attempting to recreate middle-class standards of living at lower costs (it is this class incidentally, that is the long-term target of the experience consumerism entrepreneurial sector: far from being at odds with each other, lifestyle designers are basically turning into customers of the domesticated labor-entrepreneur class, and forming the new middle class).

There are many interesting details here, and many fascinating subplots. But I'll stop here. In the concluding part of this series, I will take a shot at reading this apparently depressing situation in a more positive light, and look ahead at how the game might evolve.

Entrepreneurs Are The New Labor: Part III

In the first two parts, we covered the history of the entrepreneurs-to-labor dynamic in the Robber Baron era, and how the pattern is roughly repeating itself in our time. I promised a positive vision of the future in this concluding part.

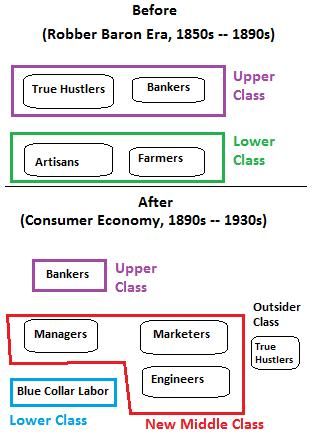

Before I do that, here is a quick visual review of the argument in the first two parts. Keep in mind that this is a complex, messy tale of two transformations that share certain features, with the second one being layered on top of the first. These are early beta versions of diagrams I am developing as part of the research for my next book, so there are certainly going to be flaws (not the least of which is specificity to the American case). But they'll do for now.

First, the before/after story of industrialization and consumerization that played out at the turn of the last century, with the associated refactoring of the American class structure:

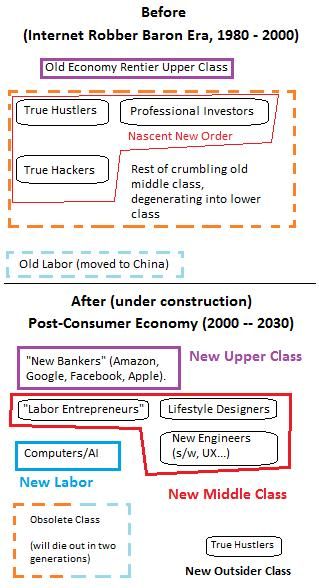

And second, the transition we are living through right now, which is still incomplete, since we are only about a quarter of the way in.

This diagram is significantly more complex than the first one, since the industrial-to-consumer transition was fundamentally simpler than the consumer-to-post-consumer. I have tried to show both the crumbling old order and the emerging new order.

For the record, I suspect I have one foot in the obsolete class, and one foot in the lifestyle designer class. I lack the drive to join the labor entrepreneur class, and the skills to join the New Engineers class at more than an amateurish level.

The major part of the story that is incomplete is the emergence of the new financial order and a class of new bankers (the J. P. Morgan type figures). What we can safely predict is that the Google-Facebook-Amazon-Apple economy will catalyze the emergence of a new financial world, both because trust in the old financial world has been completely eroded, and also because the Wall Street/DC system of today (even if were capable of operating "honestly" by some definition) is institutionally incapable of managing and regulating the new economy. The new financial order will comprise members representing the largest new economy companies, as well as members of the investor class who survive the ongoing collapse of credibility of their home institutions. Political participation in the new order will come not from nation-states or provincial governments, but city/urban political systems. More on that later.

There is a vacuum here that will be filled. This part of the story played out differently in the 1910s, when the "old" financial order of the day was simply non-existent (rather than large, mature and untrusted) until the (re-)creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913. The differences do not matter: what matters is that in both cases, there was room and need for a new financial order to emerge.

Also note that in this second picture, the new (or rather, new-new) middle class today represents a tiny, fringe population, while what I have labeled the obsolete class is actually the bulk of the mainstream economy that both Obama and Romney are currently fighting to keep alive on life support. This is a view of what the economy is becoming rather than what it is. So the pattern of emphasis may seem very strange to those of you who don't have much to do with the entrepreneurial fringe of the economy and live in parts of the mainstream economy that are still functioning.

This "becoming" may of course falter. But if there is a way out for America, it is entrepreneurs (of both the New Labor and "real" varieties) who will find it. I want to offer a positive and honest vision, not motivational cheerleading. If the diagram above does not materialize in another 20 years, we are in much bigger trouble than we think.

With that visual review of the supporting arguments out of the way, let's grab a can of paint and start the visioning.

Sam and Frodo Archetypes for the New Economy

To paint this vision we need to rise above convoluted insider debates about VCs versus LPs versus entrepreneurs versus angels vs. incubators versus Ashton Kutcher versus Shark Tank and American-Idol entrepreneurship. We also need to rise above acqui-hiring vs. "real" startup debates, and the nitty gritty of Lean vs. non-Lean models. Important as those issues are for practicing entrepreneurs (both real and labor-), they are just fussy details in the model we are building here.

To do this rising-above, we need to address two questions.

- First, how might the new laborer-entrepreneur class moving through the acqui-hiring pipeline evolve into a new institution that is recognized as legitimate rather than criticized as a corrupted parody of entrepreneurship?

- Second, what about "real" entrepreneurs, the ones who hustle for real and have the political skills and maturity to engage investors in a true balance-of-power relationship?

These might seem like a very narrow pair of questions, but in the stories we imagine for these two archetypes, all hope must rest. They are Sam and Frodo marching into Mordor. If they manage to destroy the One Ring that sustains the increasingly toxic late-stage industrial economy being run by the surreal DC-Wall Street crime syndicate (let's call it the Saruman-Sauron Axis of Evil), there is hope for a rebuilding. If they fail, things will go to hell. The #Occupy hordes at the gates of Mordor cannot do much if Sam and Frodo don't complete their missions.

The challenge for the first group is crafting and accepting a new and distinct identity, based on new labor/management archetypes, and a narrative that rejects the romantic allure of a frontier age of entrepreneurship in favor of less dramatic plots that offer more income security. Incidentally, this romanticized self-perception is also something that we've seen before: long after the Wild West had been closed off by the railroads, and the long cattle drives had ended, new-middle-class Americans living in emerging industrial towns continued to delude themselves that they were rugged frontier individualists in some vague philosophical sense. It took about 30 years for new, non-ludicrous social identities to emerge. "Entrepreneur" is today's "cowboy".

The challenge for the second group is to find sources of power with which to restore the balance of power with the investor class. The specifics of what businesses they build (the perennial "Next Big Thing" question) are less important than the rules they are able to enforce around the Next Big Game to constrain the financial class.

From this class, we can expect the second-tier innovations of the Internet Age, which will build on foundations already laid down. In the 1910s-20s, it was entrepreneurs like these who created the automobile and aerospace industries, household technologies for the new, urban nuclear-family middle class, and so forth. On top of the industrial backbone created during the Robber Baron era, they manufactured a new normal for the masses. And while no mind-boggling fortunes like those of Rockefeller and Carnegie were created by this second-tier (those levels would not be reached again until the Bill Gates era), the wealth that was created was nothing to sneeze at (and was much larger, in aggregate, than the wealth created for and by the Robber Barons in the nineteenth century).

We'll talk about Frodo in a bit. Let's talk about Sam: the laborer-entrepreneur and future middle-class citizen.

The New Labor Narrative

I am going to offer you a narrative of the modern young entrepreneur that is going to sound incredibly patronizing. But there's a point (besides snark) to telling the story this way.

This narrative, incidentally, is not an original one. You hear many versions (and specific instances) when you talk to the entrepreneurial-labor class these days. They are a partially self-aware bunch, entirely willing and able, up to a point, to recognize their own situation through a mix of CollegeHumor videos, xkcd cartoons and darkly humorous anecdotes shared at online watering holes. The partial self-awareness is a belief system delicately balanced between hipster levels of ironic disengagement, and clueless levels of kool-aid belief. The extremes exist in part to help the middle define itself.

The narrative starts with our modern-day Horatio Alger hero, straight out of college (or dropped out from one) and inspired by Seth Godin, Clay Shirky and the rest of the Internet inspiration squad.

He (and increasingly, she) has never looked at a truly ugly balance sheet or declared bankruptcy. Or navigated a business situation requiring cooperation with a more powerful adversary whose intentions are somewhere between somewhat misaligned to outright hostile. Or really failed, and acquired political skills by being played for a sucker by an older, cannier player. Or learned the value of trust-but-verify.

In other words, this is the actor who is brilliantly cast by the spinners of the Silicon Valley Grand Narrative in a role where inexperience is reframed as an asset. Our hero, the Silicon Valley bard sings, is somebody who does not know X cannot be done and therefore manages to do it. In your face, jaded-cynics.

This is the one-in-a-million redemption story sold as an expected outcome. Ironically to an audience that is prized for its statistical sophistication in other domains like A/B testing of websites.

As Gordon Gekko remarked sardonically in Wall Street II, our hero is a NINJA: no income, no job or assets. If Gekko met Shirky, he'd probably quip, in response to the latter's "Here comes everybody" line, "... so let's take 'em for a ride.".

Our hero works out of a coworking space, rooms in a hacker hostel where he desperately seeks a technical co-founder everyday (a struggle since he has little to offer in the developeronomics [2] game compared to the Googles with their buffets), goes to hackathons to pitch to increasingly mercenary engineers and designers, and stays up nights working on an incubator application. Sometimes he stands by highway ramps, holding up a sign that reads "looking for CTO".

He succeeds. He finds his technical and UX soul-mates (who have temporarily soured on Google and Facebook), gets into a top incubator, bonds with classmates, develops a deep admiration for the culture around him, with its various senior figures available for schoolboy crushes, graduates with a few angels knocking at his door, and scores a heart-warming Techcrunch story.

Along the way, he has acquired a passing knowledge, from the bleachers, of the Paypal Mafia story, watched a scene or two in the colorful drama of the Ron Conways and Dave McClures, and learned all about the Super-Angel bubble. He has met a few VCs who all insist that the other VCs don't get it. He has devoured everything that Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen and other wise demigods have to say. He imagines himself an initiate into the inner circles of Bay Area culture. He thinks he has seen the dark underbelly of American innovation (Elon Musk excepted of course, since every functioning subculture needs at least one untarnished idol to sustain hope; Musk today single-handedly sustains the increasingly wobbly belief that the startup world is somehow better than the cubicle-farm world of large corporations), but is motivated to play the game anyway. In many ways, he correctly assumes, it is the only game in town.

He is all pumped up to work hard, swing for the fences and deliver that 10x return that investors encourage him to lie about, well-aware that he is aiming for the moon in order to clear a somewhat high fence. Somewhere in his smart, Stanford-dropout head, he buries a more pragmatic hope of a 2x - 3x acqui-hire exit (with enough of a payout for a down payment on a Valley house, and a job that would have taken twice as long to be promoted into, on the "standard" career path) under layers of denial.

The prize is access to what used to be the normal middle-class script, which is now out of reach for most (the alternatives to this script are not pretty: parent basements or Afghanistan). It is enlightened, tactical self-delusion.

He achieves exactly that: a predictable, planned miss that hits a more probable, less valuable target. The little-startup-that-could gets acquired by a big company, somewhere between the seed round and the first VC round, midwifed into improbable survival by angelic quick-flip artists. The preemie struggles for life in the big company neonatal ICU (with the distraught founder-parents watching through the glass).

Mostly, it dies, but the parents survive. Some cannot wait for their golden handcuffs to come off, so they can ride the roller-coaster again. Some happily accept captivity, quietly dropping the anti-big-company rhetoric of their rent-and-ramen days.

If the case has been interesting enough, the Valley engages in another debate where triumphalist rhetoric ("this proves that the system works as it should") competes with gloomy hand-wringing ("this proves that the system is broken and real innovation no longer happens here; it is just big companies acqui-hiring, and solutions to first-world problems") for control of the narrative.

Curiously, the hand-wringing camp usually wins. Silicon Valley optimism is sustained by constant reinforcement of a rarely-attained ideal, every departure from which reinforces a sense of systemic corruption and crisis. This sense that the system is corrupt and broken, incidentally, serves a purpose that we'll get to.

Or, much more likely, our hustler deadpools. His technical co-founder and UX designer decamp to good jobs to recoup. He gamely gets up, dusts himself off, and takes another shot. Possibly at a lower-rated incubator or as a free agent. His chances go down with every crash, rather than up, in contrast to old-school serial entrepreneurs. Or he joins the lecture-blogosphere circuit, haunting the panels of the eternal calendar of Silicon Valley events, retelling his story until it grows stale. If he fails enough times, well: we'll see the first instances of that story-line playing out in a few years, as middle age hits the first generation of entrepreneur-laborers living out this story.

Lest you feel inclined to be snarky about this plot, consider this: at least our hero has some believable script to follow. There is some genuine learning, and a real shot at a life in the new economy. What he is gambling for is not the space trip and big fortune, but merely survival.

Your typical mid-career layoff, by contrast, faces a hopeless struggle for relevance in an alien economy he is ill-equipped to handle.

These are tough times. There are very few winners. Instead, there is a kind of deep social turmoil. You should be happy if you have an opportunity to access any script with some chance of survival. Even if it involves a massive amount of tactical self-delusion.

From Patronizing Sarcasm to Post-Industrial Schools

This narrative works as patronizing sarcasm precisely because there is an unacknowledged paternal/maternal dynamic to the story that is easy to make fun of.

But it is only patronizing if you take words like entrepreneur and investor at face value (it's like mistaking Buffalo Bill's Wild West shows for Wild Bill Hickock's Deadwood; farce for tragedy).

Read this instead as the tale of an average (not extraordinary and extraordinarily lucky) individual, dealt an average hand, in his/her early twenties, with words like student and teacher substituted for entrepreneur and angel. Read that way, this is merely a bald narration of coming-of-age events in an adult world. Growing up in a tough economy is hard. There are no weekend crash courses or summer programs that can magically turn a 22-year old into a functioning, economically independent adult.

In the best case, this world recognizes itself for what it is: a world of students and middle-manager mentors/teachers, working within a post-corporate ecosystem economy built around experience consumerism.

Incubators increasingly act like alternative universities. The honest ones admit what they are. A tiny but culturally significant minority of young people is abandoning college for these alternatives, which are at least somewhat relevant, and far cheaper. Rent, Ramen and being paid to learn programming beats Rent, Ramen and Student Loans incurred while learning art history.

What about the demand side? Can acqui-hiring go from being the trickle it is today to huge, broadband labor pipeline comparable to today's traditional university-to-HR pipeline?

I think it can, so long as you are willing to sacrifice your treasured notion of "job" in favor of a more flexible idea of "work".

Today's landscape is littered with incubators that are basically feeble jokes, attempting to mimic the success of Y-Combinator. These jokes will learn, grow, proliferate, shed their diploma-mill status and become real. Though Facebook and Google may employ very few full-time employees for their financial size, they do induce ecosystems that contain massive amounts of wealth. Wealth that is accessible to those who attempt to mine it with more agile tools than the rigid ones we know as "jobs".

The standardized term sheets that mark the beginning of the journey will lead on to standardized acqui-hiring terms and policies, so that the transaction costs gradually fall from M&A levels to HR levels. Large companies will start negotiating set agreements with incubators and angel studios. The distinction between angels and headhunters will blur and vanish.

Instead of transcripts and term papers, you will have a documentation of student learning in the form of Lean Startup model collateral. Or similar educational paper trails from one of the many other emerging experiential learning models.

Instead of being shunned, might-have-been-MBAs seeking out the path primarily for its credentialing benefits will be welcomed. There will be an incubator bubble upstream of the super-angel bubble. It will burst and leave behind a new education infrastructure.

I noted earlier that Lean Startup models, viewed as entrepreneurship, are somewhat unnatural things: real hustlers do not reveal their hands, cooperate tamely with investors or work out their strategies via public blogs and transparent, easily-interpreted "pivot" announcements.

But there is a category of people who openly work this way: students. Students are used to turning in homework, "showing their work", getting grades and feedback from more seasoned individuals. They are used to their output being judged by a "student work" standard of quality. They are used to deferential and respectful, rather than adversarial relationships with their teachers. They are used to turning in revisions of their work to thesis supervisors (i.e., "pivots") based on ongoing feedback. They are used to conforming to the expectations of a thesis committee.

And this is as it should be. The only time powerful adults in their prime do not slaughter young 'uns in competition is when they are teaching them.

The last point is important. I have heard many who are even more skeptical than I am of the Lean Startup model make deeply cynical remarks about the lack of evidence of success for the model, especially post-acqui-hiring (which is after all merely a procedural milestone rather than a market success).

This is simply the wrong standard to apply.

It makes no more sense to ask why a Lean Startup has not returned its investment in a truly spectacular way than to ask why a student term paper or senior thesis in college is not a Harry Potter level bestseller. Different standards apply during training and performance.

Already, in the Valley, you will find entrepreneurs with a very clear sense of how acqui-hiring valuation is done in various sectors. The numbers are becoming nearly as clear as information about starting salaries in traditional professions (last I heard, half a million per good engineer is the going rate, which would make sense if viewed as a few years worth of premium back-wages for a talented engineer, being hired a couple of levels above entry-level).

Angel investors will also recognize what they are: the equivalent of mid-career middle managers mashed up with thesis supervisors, providing stipends to apprentices on probation. They will start to see what they do -- studio startups is the current popular term -- as playing graduate school to the undergraduate school role played by the seed-level incubators.

So putting it all together, what do we have?

Early-exit, highly standardized angel-midwifed lean-legible pipelines, connecting high schools to hacker hostels and coworking/maker spaces (the new dormitories) to a two-layer schooling system that provides a vague mix of lite-liberal (Paul Graham's essays) and vocational (Lean Startup) education, and finally acqui-hiring graduation ceremonies.

After their first-blood experiences, our young heroes will live out careers shuttling in and out of different corporate ecosystems around financially massive, but HR-light platform corporations. Every few years, faced with a trough, they will retreat to developing countries as economic exiles, simultaneously diffusing knowledge globally, extending their native platform ecosystems, and recouping their own losses. Instead of a periodically refreshed resume, they will maintain a free-agent life raft in good working order, oscillating between more and less tethered modes of existence.

Collectivist institutions -- income cooperatives and the like -- will emerge to smooth out some of the natural income volatility for older individuals. The unionization of the new labor has barely begun.

What about traditional universities? They will once again become what they used to be before a century of prosperity allowed large segments of the population to go to college: preserves of the children of rentier elites. As much of the population retreats to a vocational lifestyle, only dimly aware, through TED talks, Paul Graham essays and Khan Academy videos, of the human civilizational Grand Narrative, scholarship in the old sense of the world will return as an indulgence for the few, rather than an industrial mode of knowledge production.

Art History was never meant to be a major for the masses.

If you got yourself a university education before the ongoing re-elitization, count yourself lucky. I count myself very lucky: I managed to get myself three degrees and ten very rewarding years, at no cost to myself.

Today's jury-rigged and somewhat disreputable acqui-hiring pipeline is going to get legitimized as the new education system. It is going to expand to encompass all the new engineering disciplines that I mentioned in Part II. It will blur and refactor older distinctions like liberal, professional and vocational.

And that is Sam's story. He will journey to Mordor, but ultimately settle down as a happy citizen of a new Hobbiton.

Let's talk Frodo.

Reclaiming the Hustle

So what about "real" entrepreneurship?

The "what" is becoming clear. Expectations there seem to center around some mix of green-tech, clean-tech and the Maker revolution, all swirling around in some sort of mobile-device centric high-density smart megacity. Nothing on the radar, frankly, is as revolutionary as the things produced by the first few decades of Moore's Law. The total volume of economic activity will likely be far bigger, but individual pie slices will decline.

But this stuff on the horizon is more than just the raw material for the Next Big Thing. The structure of entrepreneurship around this stuff is going to be different. The Next Big Game is more interesting to talk about than the Next Big Thing. How, not what, is the interesting question.

If the traditional entrepreneurial world is turning into a de facto education and labor market of Sams, where are the Frodos and what are they doing? The key is to ask: where are there still significant unfair advantages to be found, for entrepreneurs, that investors cannot easily neutralize?

The answer should not be surprising to those who know their history: politics. After all, real entrepreneurs are ultimately creative scoundrels, and patriotism, in the form of politics, is after all the last refuge of scoundrels.

Our young Frodo, rather than focusing on a smartphone app, is busy cultivating ties to a selected city, and learning the ins and outs of a hyperlocal political economy.

She or he (I suspect the "she" contingent will play a much bigger role this time around for a variety of reasons, possibly even a dominant role) will figure out some obscure unfair advantage in their local environment that has a political angle (perhaps zoning regulation loopholes, a city-sponsored loan program, privileged access to the traffic light system, an understanding of the school lunch system, a relationship with the taxicab union -- things like that). Unlike things like deep knowledge of an industry vertical (there are plenty of desperate, mid-career old-economy types hawking that kind of information advantage for cheap), political advantages are relatively scarce and not easily neutralized once captured.

She might even run for office, with an eye to locking in an opportunity. Her eye will likely be on a very different kind of prize: not a billion-dollar IPO, but a new institution that transcends the boundaries between market, state and civic society.

When the student loan crisis hits, or the healthcare collapse, she will be ready and positioned. It will be an era for a sort of financial civil war profiteering, sponsored by a state that is powerless to fight the metastasized cancer of a national-global financial system, but capable of providing cohorts of new city-level institution builders with the right protections, to fight in its stead.

The result will be a new social-economic-political order. It will be messy and ugly, like the decline of the Roman Empire, with local satraps asserting themselves all over the place, and a financial Praetorian Guard turning the DC-Wall Street axis into a defensive bastion.

I don't know who first said it, but "Mayors are the New Entrepreneurs" is exactly the right idea.

The Global City-State Economy

I don't quite agree with the statement in its literal form, but the political angle (and the emphasis on the city-level rather than nation-state level) is the right one to bet on. The failure of nation-state and region-based geopolitics will be remedied not by some miraculous reformation sweeping across the world, but a shift of power, in the political sphere, to cities (remember what came after the Roman empire?).

While the labor-entrepreneurs are going to flow in larger numbers through increasingly reliable and effective (and easier-to-navigate) acqui-hiring pipelines into large-company ecosystems, real entrepreneurship is going to shift to newly politicized arenas where nations and provinces have failed.

In the case of the 19th century, as the first wave industrial landscape around commodities stabilized into a regulated equilibrium, a second wave, relying on the first, took off.

During this second wave, politics and institution-building dominated the proceedings. While the first generation of Robber Baron entrepreneurs created new, ungoverned landscapes of wealth with little government presence (engaging the state mostly by enabling corruption), the second wave helped build the new political institutions required to frame, normalize and legitimize the new world order. Viewed purely as a governance mechanism in a new territory, corruption had become too inefficient a regulation mechanism for the increasingly complex new world.